|

The Campden Wonder |

|

||

| "Time, the great Discoverer of Truth, shall bring to Light this dark and mysterious Business" | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

What do we know about the Campden Wonder? How much is proven historical fact, and what merely hearsay and speculation?

To answer those questions we need to look at the sources from which our knowledge of the Campden Wonder is derived. This page summarises those sources and provides links to other pages where you can learn about the details behind the summaries.

The sources fall into four broad categories:

Primary sources are crucial to any historical enquiry. They are documents contemporary to the events under investigation.

There are relatively few primary sources available to the researcher of the Campden Wonder and those that have survived do little more than confirm what we knew already from Overbury's account. This is probably one of the reasons the enigma has remained veiled in mystery for so long.

Nevertheless, the few primary sources we have are fascinating in their own right.

According to Overbury, The Perrys were tried at the Court of Assizes in Gloucester, which was part of the Oxford Circuit.

Sadly, no record at all appears to have survived of their first trial in September 1660. The court records for this period appear to be in some disarray. This was a period of political transition, as the vestiges of Cromwell's republic were swept away and the newly restored Stuart regime took control again.

However, their second trial in the spring of 1661 has left its mark on the historical record. Cruelly brief, this reference in a primary historical document nonetheless confirms the basic facts of the case: that John Perry, Richard Perry and Joan Perry were tried at Gloucester for the murder of William Harrison at Chipping Campden, found guilty and hanged. The story cannot be, as some have suspected, a complete fiction or a hoax.

Nonetheless, this brief reference raises some baffling puzzles of its own, and seems in some ways to contradict the story as traditionally related. This challenging yet fascinating document is reproduced in facsimile, transcribed and translated here.

The names "Harrison" and "Perry" feature frequently in the earliest surviving parish register from Chipping Campden.

The family tree of the Perrys can be fairly easily constructed. However, working out how all the different Harrisons mentioned in the registers are interrelated is much more of a challenge!

Follow this link to see a list of the Perry and Harrison information that can be gleaned from the Chipping Campden parish registers, and a discussion of how that information might be interpreted.

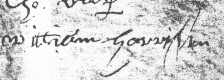

Chipping Campden possesses a grammar school, of ancient foundation. A William Harrison acted as a "feoffee" or governor of the school during the middle of the 17th century. It is very likely that this is the same William Harrison who is at the centre of our investigation. If so, then the accounts of the grammar school are another vital clue in our enquiries. Apart from anything else, they provide most of our samples of Harrison's signature (others have recently come to light in).

There are disappointingly few documents at Gloucestershire Record Office (GRO) relating to the Hicks/Noel family and their estates in the county.

However, one additional signature of William Harrison has come to light. In 1625, Harrison was witness to the sale of property to benefit Chipping Campden Grammar School (GRO ref D253/1). One of the parties involved in the sale was Sir Baptist Hicks.

The signature is slightly different from those that appear in the Grammar School accounts, but in my view they are similar enough to confirm that this was the same man: the variation is probably the result of the 30-year gap between the records.

There is a large collection of Noel papers (reference DE3214) held at Leicestershire County Record Office. Although these are still in the process of being catalogued, the staff at LRO were kind enough to allow me to inspect them. A number of interesting a previously unknown documents relevant to this story came to light.

Firstly, the document with the temporary catalogue reference of 181/19 is a lease dated 1 Feb 1649 between Julian Viscountess Dowager Campden of Brooke in the County of Rutland and William Harrison of Chipping Campden in the County of Gloucester, yeoman. Harrison is renting from his employer a house previously occupied by Honor Lilly, widow of the former incumbent of St. James, Robert Lilly as well as "two yards arrable land in Berrington also in the tenure or occupation of (blank) Lilly widdow".

Honor Lilly was buried at Chipping Campden on 24th December 1648. In her will dated 24th November 1648, she bequeaths "my lease of the Parsonage two yard land" to her daughter and grandson. This sounds very much like the same piece of land.

Was this the house Harrison was living in eleven years or so later, at the time of the events of August 1660? If so, it would seem to contradict the traditional belief that Harrison was living in part of the ruins of Campden House, possibly one of the surviving Banqueting Houses. More research is required here to try to identify the actual house in question.

The other document that I found of most interest in the collection was a rental of the Campden estates dated 1665. This is basically a list of the tenants of the land owned by the Noels in and around Chipping Campden, the rents they owed and the amounts paid or in arrears.

The first thing that one notices is that the list is drawn up by one "Mr Goodwyn". This reinforces the impression I had already received: that William Harrison's successor as steward of the Campden estates was not his son Edward, as has been popularly supposed, by John Goodwin of Combe. There is no mention of Edward in this document. In fact, I know of no reference to Edward Harrison outside of Overbury's account other than the solitary entry in the Chipping Campden Parish Registers.

The second thing that is worthy of comment about this document is that it gives us another historical reference to William Harrison himself. Under the list of "demesne rents for Michas. and All saints 1665" we find: William Harrison £11 10s 0d." and "William Harrison £0 9s 4d".

It seems possible that the fact that "William Harrison" is listed twice, once in relation to a relatively large amount and once in relation to a relatively small amount, is further evidence that there were (at least) two William Harrisons living in Chipping Campden at this time, one of high status, the other of low. The higher amount could well be that payable by the former steward, that lower that due from "old William Harrison", the weaver.

Listed amongst Goodwin's disbursements is: "Mr Harrison Brought a bill for mending walls £0 14s 10d".

The impression is very much that, three years or so after his return, Harrison is living quietly in Chipping Campden, but of his son Edward there is no sign. John Goodwin appears now to be in charge.

In 1608, John Smith of North Nibley was responsible for compiling a list of all men in the county of Gloucestershire capable of bearing arms, and of the armour they could provide.

Listed among the men of Chipping Campden is one William Harrison, weaver.

This is very unlikely to be the William Harrison at the centre of our story since a rise in social status from weaver to steward to one of the richest and most illustrious families in the land would have been truly prodigious in 17th century England.

On the contrary, this mention of a Harrison whose occupation is "weaver" is another indication that there was a local Harrison family engaged in the weaving trade and quite separate from the family of William Harrison the steward.

Many accounts of the story have been published over the years.

In 1945, E. O. Winstedt of the Bodleian Library Oxford published details of two newly discovered items of interest to Campden Wonder researchers ("Gloucestershire Notes and Queries", clxxxix pp 162). In the collection of the antiquarian Anthony Wood he had found a pamphlet dated 1662 containing an account of the story, and a broadside-ballad, also based on the tale.

Since the pamphlet is dated 1662, it seems highly likely that it was written within just a few months of Harrison's return home. The precise date of his return is unclear. In an almanac, again belonging to Anthony Wood and now housed at the Bodleian, a note of Harrison's return is written opposite the date 6th August 1662. However, the pamphlet refers to Harrison's having been absent "above two years", which would suggest a return no earlier than 16th August 1662. Whatever the exact date, the pamphlet it is probable that the pamphlet does not post-date Harrison's return by more than 3 or 4 months.

Unfortunately, neither of these works sheds any further light on the mystery itself, other than to give us an insight into the contemporary reaction to the story and give some idea of the way the rumour mill moved quickly into gear and re-interpreted events through the distorted lens of 17th century prejudice and bigotry. One feature of both these accounts is that the Perrys are assumed to be guilty, and Harrison's reappearance is explained on the basis that by the grace of God he had not been murdered by merely transported by means of Joan Perry's witchcraft to Turkey. Other than that the tale is more or less as Overbury relates it.

Indeed, having read the pamphlet and the ballad, it is tempting to view Overbury's account as his attempt to set the record straight. By 1676, William Harrison had gone to his grave having revealed nothing further of his adventures. Overbury, who may well have been personally involved in the investigation into the supposed crime, may well have thought that time had come to give his first-hand account of events, which, within only a few months, had become clouded with fantasy.

The tone of the pamphlet is moralistic. It ends with a diatribe against witchcraft and a set of biblical references to their existence and iniquity.

The full text of the pamphlet can be found here.

Also in the Anthony Wood collection at the Bodleian can be found a splendidly illustrated broadside ballad which relates the story in the form of a popular song. It too was published by Charles Tyus at the Three Bibles on London Bridge and is catalogued under reference Wood 401 (191). No printed date appears on it, but the edition housed in the Bodleian bears the manuscript date 1662.

A facsimile of the ballad can be seen on the Bodleian site at:

Although the date of the ballad cannot be proven, it seems likely that it must have been published around the same time as the pamphlet, perhaps slightly later. It is hard not to see this as Tyus' attempt further to cash in on the scandal caused by the story when it first became known. Whereas the tone of the pamphlet is solemn and moralistic, the ballad is unashamedly populist and many modern-day parallels could be drawn where popular songs have been rushed to market in order to capitalize on a recent event or phenomenon.

The ballad is set to an ancient tune known variously as "Aim not too high" and "Fortune my Foe".

The full text of the ballad can be read and the tune can be heard here.

It is from Overbury's account that the detailed story of the Campden Wonder first became known to the wider public. Although published some 15 years or so after the events that it describes, it is quite likely that Overbury was himself directly involved in the story, as the examining magistrate who questioned the Perrys.

Overbury's account is reproduced in full here with footnotes and commentary by myself.

On 19th February 1862, the "Cheltenham Examiner and Gloucestershire Guardian" newspaper published an account of the Campden Wonder, part of a series of articles on Gloucestershire history written by John Goding, a well known and respected local historian of the time.

The account is fascinating and frustrating because of the numerous ways in which it differs from the "standard" version of the story i.e. that derived from Overbury. In some instances these appear to be obvious, provable errors. In other cases, one wonders whether Goding is drawing on a source now lost to us (or, at least, unknown to me). Possibly he was relying heavily on oral tradition and folklore. There is also the intriguing but unproven possibility that John Goding might have been a descendant of Harrison's colleague of the same name. Did Goding have access to information passed down through his family?

On balance, however, I have to conclude that despite Goding's reputation as a serious historian, his account is riddled with errors and some aspects of this version of the story were either inspired by later oral tradition or may even have been complete fabrications of his own invention intended simply to spice up the story for consumption by the Victorian public.

The complete text of Goding's account, with my commentary, can be found here.

This is still the best book on the subject (until I finish writing mine anyway!). Published in 1959, Clark's book is a thorough, professional and scholarly review of the story from all angles, pulling together everything that had been published and was known about the enigma at the time. Much of the material on this website is derived from, on inspired by, Clark's work.

Also turned into a theatrical drama and a radio play, performed on the BBC in the early 1960s.

An eminently readable tale based on a solid understanding of the historical facts background to the mystery and exploiting virtually every rumour, myth and innuendo about Harrison's disappearance to construct an entertaining work of fiction.

In Potter's novel, Sir Thomas Overbury acts as the narrator and is identified as the magistrate who investigates Harrison and interrogates the Perrys.

Subtitled "A Retelling of the Campden Wonder", this is the latest version of the story to be published. Victoria Bennett tells the story from the perspective of Harrison's wife and of Bess, a young dairymaid, whom Mrs Harrison employs as her assistant.

Mrs Bennett is clearly a serious historian and has done a considerable amount of research. She is also a gifted writer. She has taken the bare facts of the story as known to us from Overbury's account and woven them skilfully together with virtually every scrap of available historical information relating to 17th century Chipping Campden, as well as some reasonable speculation and literary fancy, to produce a novel of considerable merit. My main concern is that, so far as the Campden Wonder is concerned, it may have the effect of blurring still further the dividing line between the known facts and serious history on the one hand and rumour, myth and legend on the other.

If I'm honest, it was perhaps too much of a "chick flick" for my male tastes! There is a touch of Jane Austen with a Cotswold accent about it. I found some of the dialogue using Gloucestershire dialect implausible and her "solution" of the mystery unconvincing (aren't they all?). But I'm being picky. Victoria Bennett is to be commended for a work which can only help us to understand better the effect that the Campden Wonder events must have had on the people at Chipping Campden at the time. It is well worth reading.

John Masefield (1878-1967) is by the far the most illustrious author to have been interested in the Campden Wonder.

Masefield was chosen poet laureate in 1930, but is probably best remembered for his children's stories such as "The Box of Delights" and "The Midnight Folk".

Masefield's two plays or "poetic dramas" on the subject of the Campden Wonder were published together under the title "The Tragedy of Nan and Other Plays" by Grant Richards of London in 1909.

"The Campden Wonder" was first produced at the Court Theatre, London on 8th January 1907 under the direction of H. Granville Barker. Masefield depicts Harrison as a old sot, frequently given to disappearing off on drunken jaunts. According to this version of events, Richard Perry is also employed by Harrison and has become his master's favourite. When Harrison disappears, while his wife assumes he is simply off on one of his wanderings, in a fit of pique John Perry accuses himself, his brother and his mother of having murdered him. The interfering parson brings in the Constable and the three Perrys are arrested, convicted and hanged, just moments before Harrison returns home.

"Mrs Harrison" follows on from the events portrayed in "The Campden Wonder". Mrs Harrison confronts her drunken, violent, dissolute husband after his return and questions him about where he has been. Harrison claims he went away because he was paid £300 to do so, though why and by whom is never stated. Harrison confesses that he was never more than 20 miles away from Campden and that he knew all about the Perry's arrest and did nothing to prevent their execution. Overcome by guilt, Mrs Harrison takes poison and kills herself.

Poet Laureate he may have been, respected author of children's novels also, but I have to say that I find these two melodramatic ramblings, with their laughable attempts at dialogue in 17th century Gloucestershire dialect, entirely devoid of literary merit and of absolutely no value to the serious historian and student of these events.

A more recent treatment of the tale. Even worse than Masefield's efforts, hard as that might be to imagine.